![[IAU logo]](iau_wb_thumb.jpg)

|

![[URSI logo]](URSI-logo-thumb.jpg)

|

![[Karl Jansky at his antenna]](jansky_photo_02_thumb.jpg)

|

| Jansky and his antenna. NRAO/AUI image |

![[Reber's Wheaton antenna]](Reber_Telescope_Wheaton_thumb.jpg)

|

| Reber's Wheaton antenna. NRAO/AUI image |

![[Dover Heights]](Dover_Heights_02_thumb.jpg)

|

| Dover Heights. Photo supplied by Wayne Orchiston |

![[4C telescope]](GB61-195_4C_telescope_thumb.jpg)

|

| 4C telescope. NRAO/AUI image |

![[Ewen and horn antenna]](ewen_horn1s.jpg)

|

| Ewen and the horn antenna, Harvard, 1951. Photo supplied by Ewen |

![[Dwingeloo, 1956]](Dwingeloo-1956-thumb.jpg)

|

| Dwingeloo, 1956. ASTRON image |

![[Jocelyn Bell Burnell and Cambridge antenna used in pulsar discovery]](burnell2_thumb.jpg)

|

| Jocelyn Bell Burnell and Cambridge antenna used in pulsar discovery. Bell Burnell image |

![[Lovell Telescope at Jodrell Bank]](site_1594_0001-500-334-20180316163019-thumb150.jpg)

|

| Lovell Telescope at Jodrell Bank. Image © Anthony Holloway |

![[Wilson, Penzias, and Bell Labs horn antenna]](wilson-penzias-horn_thumb.jpg)

|

| Wilson, Penzias, and Bell Labs horn antenna. Bell Labs image |

![[6-m Millimeter Radio Telescope in Mitaka, Japan]](6m-thumb.jpg)

|

| 6-m Mm Telescope in Mitaka, Japan. NAOJ image |

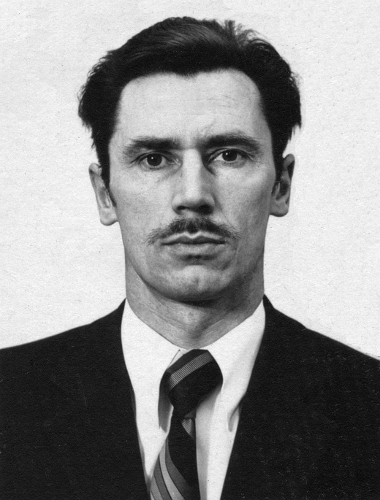

Gennady Borisovich Sholomitsky

Gennady Sholomitsky was a pioneer of radio, submillimeter and infrared astronomy, Head of Laboratory at the Space Research Institute of the Russian Academy of Sciences.

G. B. Sholomitsky was born on February 6, 1939 into the family of an accountant in Petropavlovsk-Kamchatsky, at the Far East of the Soviet Union. In a few years, the family moved to Kuybyshev (now Samara) in Central Russia, where Sholomitsky lived with his parents and younger brother until it was time to choose the future profession. In Moscow, where he arrived with two gym weights in his backpack and some pocket money his mother had sewn into his belt, Sholomitsky was admitted to the Faculty of Physics of the Lomonosov Moscow State University (MSU).

He appeared in science at the right time and in the right place, as the late 1950s - early 1960s saw rapid progress in astrophysics and space exploration. In 1962, Gennady Sholomitsky graduated from the Astronomy Department of the Moscow Lomonosov State University and began his postgraduate research at the Sternberg Astronomical Institute (SAI) under the supervision of Iosif Shklovsky. As Shklovsky once put it, you could say that Sholomitsky was a true scientist simply by the way he was holding a fresh issue of Astronomy Letters in his hands, his face lit up. He was assigned to lead a SAI group of young enthusiasts at the new Deep Space Communication Center near Evpatoria in Crimea. Their task was to learn how to work with unique large antennas that had been installed there. The antennas were to be fitted with high-sensitivity equipment, and observing techniques were to be developed. Many things were being done for the first time. This was the period of rethinking the surrounding world and transition from the classical, mostly optical studies of astronomical objects to the studies of physical processes that rule the Universe. One of the focuses of new astrophysics was synchrotron radiation, generated by charged relativistic particles moving in a magnetic field.

Sholomitsky investigated the peculiar spectra of a sample of radio sources in the centimeter and decimeter bands, paying particular attention to the high-frequency spectral excesses that corresponded to young, high-energy particles. In order to sharpen the angular resolution, the observers employed the method of lunar-occultation. The observing equipment included high-sensitivity maser and parametric amplifiers tuned into wavelengths of 8 and 32 cm. The occultation observations of 3C 273 on June 17, 1964, revealed two structural components: a jet with a power-law spectrum and a compact source with a flat spectrum, the latter to be soon identified as the first known quasar. It was difficult to imagine, however, that objects of that nature had strictly steady-state streams of particles, and, consequently, their radio emission must have been variable. In those years, this assumption evoked a smile in the best case. Standard mechanisms for radiative losses of radio electrons could assume variations which were comparable only to the lifetime of a long-living human. With his inherent drive, Sholomitsky tackled this problem, which cast doubt on the ideas of many accomplished scientists. The results of such studies would be very difficult to defend. However, Sholomitsky was concerned more with the solution of the fundamental problem rather than with defending a thesis. He chose one of the characteristic objects with a peculiar spectrum, CTA 102. His search for variability of radio sources was successful. The result was so unexpected that only a few were ready to believe it. Due to the fact that the facility used for these observations was highly classified, Sholomitsky was unable to publish traditional for radio astronomy work detailed description of his instrumentation. The lack of these details and very unusual physics behind the observed short time-scale variability resulted originally in some skepticism among radio astronomers around the world. However, a few years later, the results by Gennady Sholomitsky were confirmed at many radio observatories around the world. The variability of extragalactic radio sources discovered by Sholomitsky is one of the milestones of the 1960s, the Golden Decade of radio astronomy.

In the 1950s - early 1960s, radio astronomy suffered from insufficient angular resolution. A solution was suggested in 1962-63: Very Long Baseline Interferometry (VLBI). Gennady Sholomitsky took part in the development of VLBI methodology together with Leonid Matveenko and Nikolai Kardashev. Their paper, published in 1965, gave the first description of VLBI - the technique which holds the record in angular resolution across the electromagnetic spectrum for more than half a century.

In 1968, Sholomitsky defended his candidate's thesis (an equivalent of PhD). Immediately after the defense of the candidate's thesis, I.S. Shklovsky invited Gennady Sholomitsky to the Space Research Institute of the Academy of Sciences of the USSR to set up a laboratory of submillimeter and infrared astronomy. Sholomitsky designed telescopes, being occasionally ahead of time and existing engineering capabilities. Inspired by his enthusiasm, the leading domestic companies designed a cooled space-borne telescope. He refined the measuring techniques and procedures for high-altitude conditions in the Pamir mountains and on aircraft, and explored the possibility of submillimeter observations at the Vostok station in Antarctica. In 1993, Sholomitsky defended a doctoral thesis on submillimeter astronomy.

Despite being very busy with large space exploration projects, Gennady Sholomitsky continued his astrophysical research. Together with colleagues from West Germany, he carried out a series of observations with the 6-meter telescope at the Special Astrophysical Observatory in the North Caucasus. He devoted his time to observations of scattering of the cosmic microwave background radiation by clusters of galaxies (the Sunyaev-Zel'dovich effect), predicted the generation of scattered polarized light - a halo around quasars, and performed the first series of observations aiming at this observational phenomenon.

Sholomitsky also paid attention to the problems of ecology; he studied aerosol-dust pollution of the atmosphere in large cities. For this work he received a patent in 1993. He later developed methods of space debris detection and cleaning up the polluted circumterrestrial space.

The results of Sholomitsky's studies are presented in more than 100 publications in the leading professional journals.

In 1999, he worked on the next series of observations in Crimea with the Zeiss telescope, edited and submitted a paper on the first results of large-scale polarimetric studies of halos around galaxies, and began working on an article on the history of VLBI. However, he passed away unexpectedly on June 17, 1999 at the age of 60 before he could fulfill many of his plans and ideas.